Regular readers may recall an August 2023 post featuring the October 1987 issue of Personal Computer World, and might be wondering why I'm returning to the same publication and the same year so soon. Well, good people, it's because of the cover star of this particular issue and the amount of time it took to get my hands on it.

|

| This, dear reader, was the dog's back in the day. |

Yes, it's the first look at the Acorn Archimedes, packing in Acorn's ARM processor for a desktop costing less than £1,000. There's other stuff too, but as a massive Acorn/RISC OS fan, I've always wanted a copy of this issue and, after several abortive eBay attempts (including one crapping out at north of £20), I managed this example for a tenner. So let's have a look a what's inside.

It's not all Acorn, by any means, and the review of Atari's PC raises more than just eyebrows, while Psion's Organiser II gets a full airing. There's software tests and the usual columns, and a very intriguing look at the Transputer. Hmmm...

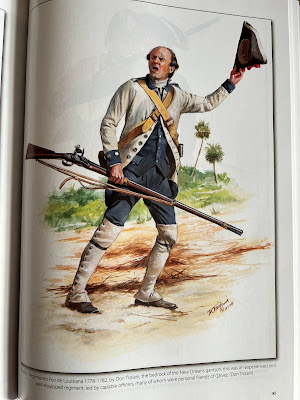

|

| It took a couple more years but the OS did improve. |

News was a bit slow that month so we're straight into the Acorn review. A pre-production machine, this wasn't entirely representative of the final hardware but was good enough to run some tests on, and by 'eck as like, it were fast! As Mr Pountain evangelised, "the A500 [the designation of this development system] felt like the fastest computer I have ever used, by a considerable margin." And so it was, capable of blitzing through anything you'd care to through at it (mostly synthetic benchmarks here), and all for under a grand exclusive of VAT. Yes, the base A305 (single floppy, 512k RAM) was £799, and a colour monitor added another £200. You could cheap out with a green mono monitor for just £50 but why limit this technicolour beast in such a manner? A 1MB model was £875 sans display, while the more expandable 1MB A410 (with a hard disk controller but no actual HD) took you up to £1,399. For the true power user, an fully decked out A440 (4MB RAM, 20MB HD) would take £2,299 from your wallet. Well, way more, as a monitor and VAT would see that total reach nearly £2,900! There again, an IBM AT from your average dealer was north of three grand, and a hard drive equipped Mac SE was about same price as the A440. Of course, not everything was as expensive, and it was Atari that now stepped up to the DOS wicket to see what they could offer against the value-packed Amstrad clones.

|

| Could this have been a go-er? No. It couldn't. |

A chance of death, it seems, as their rather flimsy (and "relatively mediocre") machine had an unshielded and unprotected power supply. Take the hint, buyers, DO NOT open this machine. Not that you could do much with it once you have dared to take the cover off as there were neither expansion slots nor drive expansion options (despite some labelling that hinted otherwise), but you could upgrade the memory to 640k (from the base 512k), as well as add an 8087 maths co-processor. The socket for the latter was under the power supply, so perhaps not then...

|

| Many |

It's not all doom and gloom for the Atari - its graphics capabilities were rather good for the time, stretching from MDA to EGA. Yep, the presence of 256kb of video RAM meant 16-colour 640x350 was just a connection away! That sounds sarky, but this machine (albeit with a mono monitor) could have been yours for £499 VAT inclusive. In other words, a cheaper headline price than Amstrad's popular PC1512. However, that had space for three expansion cards, and adding a hard drive card was relatively easy. You pays your money and all that jazz, but a single drive PC even in 1987 was just too limiting.

|

| Allegedly the most fun you could have one handed back in 1987... |

The other big review this issue is for the Psion Organiser II, a nifty little handheld computer that I wrote about for Pixel Addict magazine in issue 8. It's a cracking little device which could do the job it needed to back in the day, albeit with a keypad that took some getting used to. It's well liked here and it was a success for Psion at the time.

|

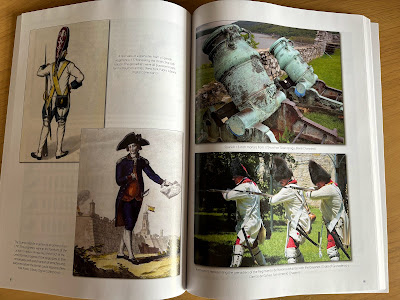

| There has to be a "What If...?" out there about this, surely? |

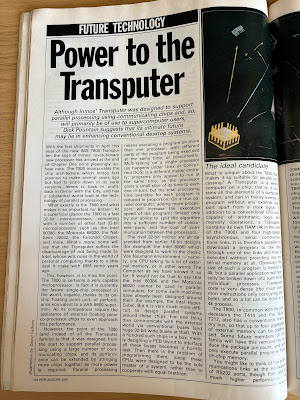

The feature on the Transputer is something else though. Promising a breakthrough in computing power beyond the contemporary constraints of processor technology, it offered super-computer levels of floating point power and easily scalable parallel processing shenanigans. There were issues though, primarily the lack of a mainstream operating system (and by default bugger all software), and a question of who would need such power. The author notes that a Z80 was more than enough to handle a word processor on Amstrad's PCW8256, though they go on to say that in the future, animated graphics would need the power, as well as a Hollywood director to make the game. He jests but...

GEM Desktop Publisher got the thumbs up (good enough for the asking price of £295 ex VAT), whilst a round up of dBase compilers would be of use to someone... somewhere... As will the piece on the then recently announced OS/2 from Microsoft. It was never destined to end well, but the conclusion at the end of the piece deserves its own screenshot.

OS/2 success and 640k... Indeed...

Guild of Thieves received an alright verdict in the Screentest section, and gamers were also catered for in Program File, where an Adventure Creator was detailed over 16(!) pages of code in very small text and varying degrees of contrast. It gave me a headache just glancing over it.

|

| And they blamed porn for blindness in the 80's... |

To the adverts now and DOS PC's were pretty much split into two camps - the XT level 8086/8088/NEC V20 machines that gave you a basic PC starting from about £450 ex VAT before heading up north of a grand. The more you paid, the better you got, with a mono hard drive offering to be had for not quite four figures including VAT. If you wanted EGA graphics though, add another £400 plus on top. The other camp was the AT spec of machines - 286 processors, high density floppy drives and EGA colour if you so desired. Hi-Voltage would sell you an SBC-branded 286 with a 30MB hard drive and an EGA colour monitor for £2,199 ex VAT! You could get cheaper, but not by much, and this pretty much explains the success of the ST and the newly introduced Amiga 500. If you wanted an actual IBM PC, Compumart had the real deal XT starting from £1,100 for a mono machine, whilst your new-fangled AT with a colour display was £3,170! At least they included a keyboard, mouse and DOS for that. Sheesh!

|

| Danger! Danger! Hi-Voltage! |

"Portables" were a thing as the ad for Toshiba machines demonstrates below. Not sure if they were practical enough, but hey, you could tote around your work computer if you so wanted to (and if you had the muscles). Compaq was also an option, as were several other clone manufacturers, but most followed the luggable concept with built-in CRT displays rather than a portable as we would know it.

|

| They could be carried... with some effort. |

As Acorn were star of the cover show, they decided to advertise their wares with what can only be described as a... marketing choice...? I get it, they went for the Greek connection, but when you have a machine that offered graphical capabilities beyond its contemporaries, a mono advert does seem kinda weird.

|

| Could they not even afford a colour ad? Probably not... |

Apple does something a little different, with a splash of colour for their logo if nothing else. There again, with Mac prices back then, did it really matter? ATT Peripherals Corporation had the Mac Plus at £1,550 ex VAT, a dual floppy SE for £1,875, and fully pimped out SE with 20MB hard drive for £2,450 ex. You may think pricey, yet only slightly more expensive than the monitor-less Apricot Xen 386 below it - but check out the addition of an EGA card and display. An additional £924 on top of the £2,350 for the desktop! Unlike the Mac though, the use cases for a 386 in 1987 were pretty extreme, thus balance was restored to the Mac/PC price comparison. Before we leave ATT though, have a gander at the DTP package. As a sign of how things changed between then and even the beginning of the following decade, a DOS-based DTP bundle including a 286 machine with a Canon laser printer was £4,300 ex VAT. Trick it out with colour and a 386 and you were looking at nearly seven grand! You'd have kept Nigel Lawson happy though, with VAT at 15%...

|

| For a price, you cheeky sod, for a price... |

For the next Magazines of Yesteryear, I think a change of decade (just) is in order. We shall jump forward to 1990 and a rather more slender publication. I shall leave you with some more of the ads - starting with ATT Corporation Ltd... (and a final question of Atari that I don't think shlud be asked in polite conversation...)

|

| Not AT&T, obviously. |

|

| Other formats were available. |

|

| Your cheapest business dot matrix printer: £444 ex VAT! |

|

| Can they be "hotlines" if there's only one? |

|

| I mean, it's a question... |