The last issue of What Personal Computer? I looked at carried the news of Amstrad's latest attempt to become relevant with a 286 in late 1991. That didn't work out too well for them, but what about the company that began the whole x86/DOS shenanigans in the first place? In the September 1990 issue, Big Blue provided an answer to the question: what PC do you sell to the average consumer?. Well, they thought they did, but at least it got a cover photo. And yes, kids, computers were both as beige and as downright ugly back then too.

The main news item was rapidly decreasing PC prices. Elonex were knocking £200 off their 386V/33 (a 33MHz 386 system as if you couldn't tell, featuring the EISA (Extended Industry Standard Architecture) bus - an open competitor to IBM's more strictly controlled MCA (Micro Channel Architecture) bus), taking the headline price down to £2,295 ex VAT for the 40Mb HD mono model. Similarly, their 286 40Mb VGA colour system was down to £1,145 ex, and the 386SX equivalent comes in at a "mere £1,395." Mere, they say? Olivetti took £100 off both their PCS86 and PCS286 ranges, whilst Gandlake (1990's computing equivalent to Accrington "Who are they?" Stanley) priced their entry 286 at £899, a £96 cut.

In other news, DR-DOS was hitting version 5, adding additional memory management for those 640/384Kb blues, as well as a disk cacheing ability to improve disk access times. A new release of MS-DOS was rumoured but the report notes that it probably wasn't going to be called MS-DOS 5. Oh, what little faith yea had in imaginative marketing types... MS-DOS 5 would land in June 1991. Apple also gets a mention in the news - a new model rumoured to be called the Classic, which did in fact hit the market in October 1990.

The first feature we get to is the Bunch Test, this month comparing laser printers under £2,000. You may snigger at the back, but in 1990, that was budget level. The winner was the Panasonic KX-P4420, rocking a £1,395 price tag, quick performance and extra fonts. It only emulated a LaserJet (the then-defacto standard for laser printers), and was a tad chunky, but was otherwise good enough to take the crown.

The cover star is next, and it really does look nasty. Expansion by additional slices can work (the pinnacle of which was Acorn's Risc PC in 1994), but here it just looks clunky. That second, 5.25" floppy, looks like it'd be blocked by the keyboard on smaller desks, yet the 3.5" drive, for all of its weird angular looks, defined IBM's aesthetic of the period, and I still kind of like the cut of its jib - just not the box it's attached to. As for the rest of the hardware, this home-targeted machine was merely average. A 10MHz 286, 3.5" 1.44Mb floppy, a 30Mb hard drive and VGA graphics. However, the negatives outweighed even these slight benefits. Standard RAM was 512Kb, although you could buy a board with an extra 512Kb to experience the joys of that 640/384Kb split. Two proprietary slots (IBM, proprietary? I'm shocked, I tell you, shocked!), could handle a modem and a joystick/audio card, but if you needed 16-bit ISA slots, an additional expansion box could be purchased. No tools were needed for fitting said box, but as it followed the design footprint of the base unit, full length cards were excluded. The final verdict? To quote the boxout, "If you know enough about computers to read this mag, you know enough to leave the PS/1 alone." Ouch! It didn't help that UK pricing wasn't confirmed either, and the recently launched Amstrad PC2286 could give you a larger hard drive and monitor (14" instead of 12" - back in those CRT days, the extra inches often counted), for around a grand excluding the Chancellor's cut.

A feature on the NeXT machine posits that next-gen PC's will probably look like the NeXT Cube, as well as offering a new GUI-based operating system. A complete package offered 8Mb of RAM, a 40Mb hard drive, 17" Mega Pixel (their words, not mine) display and a 230Mb capacity optical drive for £6,495. At that price, the GUI may be wondrous, but Macs were cheaper (well, some were), and Acorn had RISC OS on its £649 A3000.

286 workstations go head to head on page 54, with Mitac and Compaq both trying to justify why you should spend £1,399 and £1,895 respectively. They're mostly evenly specc'd - the Mitac edges out the Compaq with its 12.5MHz chip (as opposed to 12MHz), and it's extended VGA display options (800x600). It's a smidge faster than the Compaq but the latter has the option of up to 13Mb of RAM - at a price, of course - £2,730 on top of the base config. The reviewer does note that corporate buyers would go for the Compaq name, but as he's not a large corporation, he'd go for the Mitac, and I can't say I blame him.

CAD packages receive a round up (EasyCAD 2 for the win), before we reach the reviews section, the most notable of which is the Sygnos 68 LCD monitor. For £799, you got an 8 x 6 inch mono VGA (black on white or white on black) display. Whilst very restful on the eyes for text entry, ghosting made it marginal for anything else, but the review notes that it is recommended to pregnant women worried about CRT display radiation. Yes, that was.a thing. and it wasn't until 1992 that the Swedish Govermnent legislated for the maximum amount of radiation a person could experience at half a metre from the display - MPR II was your friend. A preview of the next issue promised a trio of 386's and a round up of accountancy packages, Woohoo, I near nobody cry.

As is expected, we now come to the adverts, and it's relatively slim pickings as WPC? was not the tree destroyer that PCW or Computer Shopper were. Diamond Computers are the first major advertiser, offering A500 trade ins for Amiga 2000's. The new A3000 was also on sale, but starting at £2,499, it was a niche machine for most. Page 14 continues the Commodore interest with a double spread on their PC Starter Packs. You could save up to £300 on one - naturally, that was the most expensive PC30 model. The small print points out that the PC30 was £1,199 ex VAT (£1,378.85 inclusive) for a colour VGA 286, and the main blurb about getting sorted for less than £500 was for the 8088 powered mono dual floppy PC10 at £499 ex, (£573.85 inc).

MBC were selling 8088-powered hard drive equipped VGA models for £845 inclusive, 286's for £995 and a 16MHz 386 for £1,245. These had tiny hard drives though, so extra money was needed to get up to 40Mb, but MBC were a rarity in advertising VAT inclusive prices.

Time Computers were shifting Amstrads, Olivettis and Tandons. As noted above, Amstrad's 2286 was a budget wonder. The 12' High-Res VGA colour option sneaked under a grand ex VAT, and the PC1640's replacement, the 2086, could give you proper VGA colour for three figures including the Treasury's take. The pesky hard drive issue was sorted by this point, but the damage to Alan's reputation was done.

Page 68 offered an ad from American Research Corporation of Croydon, Surrey. A 386SX laptop, it boats of "a complete business partner, ergonomically designed, weighing a slim 15.4lbs." To borrow from Senor Inigo Montoya, they kept using those words but I do not think they mean what ARC think they mean. Looking at the pic, "slim" and "ergonomic" seem to be doing as much heavy lifting as that NFL player.

Silica make an appearance with Atari's ABC PC compatible. Sadly, the headline £899 (ex VAT) for a 30Mb and EGA toting 286 fails to point out that the EGA is mono. Colour takes the price up to £999 ex, whilst the Turbo model with SVGA adaptor, monitor and fast disk controller is a much more considerable £1,299 ex. What Atari should have been doing at this point was try to rescue the ST from its fate, but no, they pissed around with DOS compatibles and the Portfolio (Silica add on page 85 - a terrific little handheld for the price, by the way, but not really a core product for Team Tramiel) instead. The same comment could be aimed at Commodore as well.

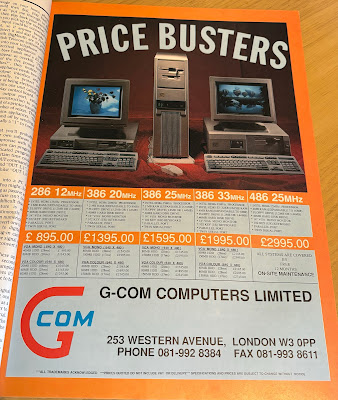

If you were really flush, however, you could grab yourself a 486. G-Com Computers offered a good selection of PC's - that 286 wasn't bad even considering the added cost of colour VGA, the 386's provided more power with the caveat that really there was nothing much yet the typical user could take advantage of, but that 486... £2,995 ex for a mono system. You were paying for the power, most surely, but it was just for bragging rights.

What this issue demonstrates, especially when compared to the last PCW post, is that the DOS PC market was evolving. Sure, it wasn't totally out of the mid-80's business machine category just yet, but it was getting there, a point easily made by the presence of VGA graphics on machines costing way less than a grand inclusive. Hard drives and faster processors would rocket up the price, but a key element of the DOS machine - the display - was now capable of standing against the more home orientated 16-bit competition.

It would take another year before the 286 hit the mass market, and by then, a grand in cash would buy you a 286 with VGA, hard drive, and with a smidge left over for a sound card. Compare and contrast to the Amiga and ST - both were still cruising off the glory days of the 68000 and a TV. Arguments over operating systems would continue (and worthy of some consideration), but the point I am making here is that what might have seemed like a completely outclassed business only machine in 1987 was, by late 1990, developing into the supreme home computer format. Combine that progress with the frankly crazy corporate attitudes of Commodore and Atari to their homegrown formats, and it wouldn't take much for those who were looking for the best thing in computer games to gravitate towards the PC.

Next time, a journey further back into the mists of UK computing journalism, with a look at an issue of Personal Computer News, a weekly publication from the early to mid 1980's.