Sunday, 22 December 2024

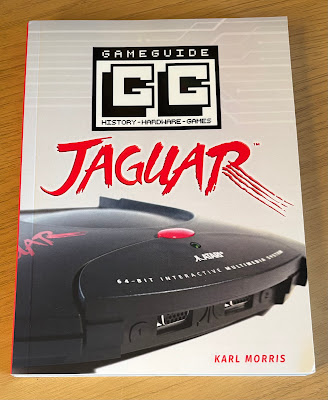

Game Guide to the Atari Jaguar by Karl Morris - Book Review

Sunday, 15 December 2024

Blake's 7 Production Diary Series A by Jonathan Helm - Book Review

|

| What a cast! |

|

| You know he's judging you... |

Sunday, 1 December 2024

What if... RISC OS part three

This is the third of three articles published in the Wakefield RISC OS Computing Club newsletter last year. The articles focussed on three key years for the Acorn Archimedes and its successors - their original launch (with the Arthur OS) in 1987, the introduction of the A3000 (and RISC OS) in 1989, and finally, the belated attempt at the wider UK home computer market with the A3010 in 1992.

But what if...? (cue wibbly wobbly screen effect...)

1992

Despite the growing popularity of games consoles such as the Sega Mega Drive and Nintendo SNES, Commodore are going just great, at least volume wise, with the UK arm expecting total Amiga sales of 300,000 machines that year. A600 sales are a bit meh, and certainly not at the numbers of its predecessor. The A500 averaged 25k units per month, the new kid on the block only 16k per month between May and August of '92 (5). With the announcement of the A1200 in the UK on October 21st, the Amiga has a much needed tech upgrade, especially pertinent since the core A600 spec is dated and not far removed from 1987's A500. That model takes a price cut from £399 to £299, and legacy high end models see prices slashed: the base A3000 can now be had from just £1,299 instead to its previous price of £2,999! (6) It all looks great, except for one thing...

The A1200 is delayed, with only limited shipments reaching the UK by December. A combination of quality control issues and a failure to contract manufacturing in Scotland due to a liquidity squeeze within the main company means that instead of the expected 70k units, Commodore UK has just 500 to sell before Christmas. The presence of the new model, alongside some remaining stock of the much more expandable A500 Plus (a model whose production ended months prior), means that the A600 withers, with fewer than 50,000 machines making it off the shelves in the three months running up to the festive period. The A1200 situation improves slightly in the new year, but missing the all important Christmas period is a huge blow not only to Commodore UK, but also to the parent company.

Atari are unable to capitalise of their traditional foe's woes. Their next generation machine, the Falcon, also misses the Christmas window. That it also happens to be nearly twice the price of the A1200 matters not. For that amount of money, you are also looking at a reasonable 386 DOS/Windows PC. Not even a pre-emptive price cut of the steadily aging STE to £199 can save them. For less than that, you can buy a SNES or Mega Drive if gaming is your thing. There are even plans to re-introduce the practically archaic STFM into production for an RRP of £159, with wildly ambitious/what the hell were they drinking sales figures of 150,000 mentioned. Never mind that they'd stopped making the STFM back in early '92 (7).

Acorn, however, do step in to the breech. The A3010 is a 1992 Christmas success. A solid effort by Dixons and other retailers desperate for some sort of cheap-ish home computer gives the machine a high street push, whilst advertising in ST Format (8), CU Amiga (9) and Computer and Video Games (10) targets those looking to either buy their first home computer (but not wanting re-heated mid-80's spec kit) or those wanting to upgrade said kit but can't buy it for neither love nor money. It's not huge numbers compared to the competition's usual figures, mind you, some 120,000 units by the time the dust settles(11), but it's enough to dent even Commodore's seeming omnipotence. Even the negativity of having an order backlog in the New Year doesn't hurt, with some mildly successful spinning of the shortages adding to the computer's allure.

1993

The fallout from Christmas 1992 is apparent almost immediately. There is a rush of ports from traditional Amiga and ST developers to RISC OS as another source of games buyers arrives on the market. At a time when selling 10,000 copies of a game meant it was a big hit (and even 5,000 was acceptable) (12), getting even the latter figure on top of existing sales (and on a format that is relatively starved of games) is worth chasing. It's also a less capital intensive publishing environment than the console market. Following on from that, publishers begin to include RISC OS versions of new titles, some even taking advantage of the platform's capabilities, especially 256-colour graphics, aiding many a PC conversion. Much is also made of the fact that the Acorn's pack a 1.6Mb high density floppy which certainly helps with multi-disk releases.

Despite a rush of new sales and the aforementioned £159 STFM, Atari's bullish talk is beginning to sound like marketing bollocks. 100,000 Falcons (13) in 1993 is as believable as the 150k new build STFM's, and as the summer draws to a close, quality control and supply issues mean that only 7,500 Falcons are in the hands of users (14). The financials for Q2 fail to mask just how far the company has fallen: net sales of $5.7m leading to a net loss of $6.6m compared to the same quarter in 1992 (15). Q2 was always expected to be a quiet business period, but even so, the silver lining of $35m in cash reserves doesn't hide the fact that it won't take long to burn through that. The company focus shifts to the Falcon and their new console, the Jaguar. Even that doesn't go well, with only around 1,000 consoles hitting the UK in December (16). The STFM revival is never mentioned again.

Commodore, well, it's just a shit show and a half. The results for 1992 are dire. Revenue drops from that billion dollar mountain to $725m, and the corresponding operating loss of $86m stuns pretty much everyone outside of the C-Suite. The decision is made (once again) to double down on the Amiga, with every effort going towards the A1200/A4000 duo, as well as the CD32 console. That doesn't go well either. Having sat for too long on the A500/B2000 platform, the company are way behind the technology curve and having to push to make up for it. Already in a rushed development cycle, and with ongoing arguments about whether to hold off the launch until 1994 as per the planned roadmap (17) in order to have a decent software line up or scramble for whatever revenue they can get, the console is announced in May 1993, with a trickle of production units reaching stores that September.

It's a disaster. What units that make it to stores do sell, but there is a dearth of CD32 specific games. A1200 ports make up most of the announced titles, yet there are precious few of those as the A1200, already struggling, now faces competition from its console brother as well as the A3010 and the PC. Not that this matters, as by November 1993, Commodore's problems finally catch up with it. The parent company is declared bankrupt after finally running out of cash and the disposal sale is completed early the following year.

Acorn, however, are holding their own. A revitalised software stream and steady sales means that their financials announced mid-93 show a profit of £12.6m from a turnover of £72.1m, and a growing realisation that the platform isn't just for games. Windows PC's are a threat, but even now, a decent spec'd 386 is still the best part of a grand. The decision to standardise on a 2MB A3010 model in mid-93 pays off for Acorn, as does a price cut to £349. Margins are tighter, both for dealers and Acorn itself, but in the UK at least, sales of the 32-bit machine rockets passed the 350,000 mark by the end of the year.

1994

As the new year hangovers clear in 1994, there is much for fans of RISC OS to rejoice, some good news for Amiga users, and little comfort for ST owners.

Atari are desperate and the fire-sale of STFM's and STE's adds pittance to the coffers. The Falcon hits £495 but there is little software available and the company's eyes its dwindling resources as it tries to make a success of the Jaguar. Despite lip service to the contrary, Atari as a computer manufacturer is all but done. The computer range is sold off and, in an effort to define the term "Forlorn Hope", the last roll of the dice is made for the Jaguar.

There's better news for Commodore fans as the UK management team buyout succeeds in gaining control of what assets are left. A crash program is put in place, doubling down on the CD32 and the A1200, whose base price for Commodore manufactured stock hits £249, whilst the last of the A600's go for £149. The A300 is announced, coming in at £249 for an AGA-equipped CD-capable (an add-on drive appears from third party suppliers for CD32 compatibility). The CD32 continues to sell for £249, and a new licensing program is launched to bolster revenue. At the higher-end, the Amiga 4000 is retained. The future looks promising, as long as they can sell hardware, and there is bullish talk of a next-gen chipset. Paging Mr Osborne...

Acorn begin the year caught somewhere between shock and swaggering relief. The A3010 is selling as fast as they can make them, forcing some cannibalisation of the A3020 supply. That doesn't affect school sales too much, with the (Acorn) A4000 picking up the slack despite initially being advertised purely for secondary schools. A brief diversion in to making a home console is considered before sense returns to the room and a proposal is made to support the 3DO. This isn't as daft as it sounds, as the launch of the Risc PC in April means that there is now an expandable, CD-equipped tower running an ARM 610, for £1,500. Ouch for the pocket, but a hell of an upgrade for early A3010 adopters, aided by a trade-in scheme to push existing owners towards the higher spec. The presence of a guest CPU slot (and some fancy engineering) makes the 3DO card possible, and in November 1994, RISC OS users have the option of playing the (limited but slowly growing) range of 32-bit console titles.

However, the company isn't resting on its laurels, as it is apparent that the A3010 will struggle in 1995, not least because it will fall foul of new electronics legislation. They are also aware that the traditional market for home computers is slowly disappearing. The rise of the Windows PC, initially 386 and now 486-powered, has altered the dynamic of buying a computer. Budgets now stretch into the low four figures for a capable gaming PC, and the market is awash with consoles. There is also an acceptance that your bog-standard television is of no use as a serious computer display and that, just like the PC, future machines will require a dedicated monitor. As 1994 concludes, the consequences of this realisation reshape the home computer arena once more.

Acorn strike with two ARM 7500-equipped desktops. One offers a desktop case with space for a CD-ROM, but includes a hard drive and monitor as standard. The other matches the styling of the A3010, but with included hard drive and TV/VGA connectivity. An external CD-ROM available for £150 proves a popular add-on. Existing owners have a clear upgrade path, whilst developers have hardware that can sustain ports from the PC world as well as console conversions. Indeed, throughout 1994 and 1995, RISC OS and the 3DO see a cross-pollination of titles. Rather than just Star Fighter 3000, there is enough software support to benefit both platforms. The lack of a dedicated 3DO card for the A7000 series does hurt the concept, but remains a handy upselling tactic for the Risc PC. Not enough, of course, to save 3DO from the Sega Saturn or Sony's PlayStation, but every little helps.

|

| What could have been... |

To boost sales, there is a trade in scheme that takes £150 off a new A7000-series machine, with the older computers handed in re-cycled for emerging markets. Acorn now have a trio of machines aimed at the low, mid and high level user, and news of a laptop based on an existing Olivetti design (18) demonstrates that the once majority shareholder still supports it's British off-shoot, and profits of £15.5m from a turnover of £85m are ample evidence of the company's success.

1995

After another brisk Christmas period where Acorn announce their 1 millionth RISC OS machine sold, it becomes apparent that the pace of sales is beginning to slow. The breakneck speed of the PC's advance has meant that by the summer, even the billy basic 486 can be had for the same as the low-end A7000 CD-equipped model, and as Windows 95 arrives, it becomes clear that Acorn no longer have the upper hand when it comes to a price/power/capability comparison. There is little despondency though as the platform appears to have more than enough momentum at present.

The Risc PC700 arrives to pep up the hardware offerings, and discussions begin about the future of the platform. The new laptop proves a hit, and whilst there are signs that the company is beginning to lose the education market to the Wintel combination, the relatively buoyant home market in the UK brings in the money. It is acknowledged though that this is a shrinking percentage of an ever growing pie of general users. Even so, profits of £13.2m off £76m revenue are a reason to celebrate.

Less good news for Amiga fans as "Neo-Commodore" closes its doors in September. Despite valiant efforts with the CD32, it becomes clear that it isn't a competitor in the wider console wars, selling less than half the numbers of even Atari's ill-fated Jaguar. Against the new offerings from Sony and Sega, it isn't even a joke. There are rumours of a successor which would beat the newcomers, but time (and finance) isn't on the their side. The A300 similarly failed to sell against the vibrant Acorn machines, and despite a licensing scheme that saw the Amiga brand on everything from mugs to towels (the PJ set was the nadir), the company's biggest problem was that it just could sell enough computers. It didn't help that the AGA tech underpinning the range was only just competitive in 1992 and looking increasingly antiquated in 1995. Talk of more advanced machines dampened enthusiasm for the current range, and squeezed by more successful consoles at the low end, Acorn in the middle, and by PC's at the top, it was doubtful even with that £50m investment fund they could have succeeded.

1996

It has been a good run, but the seasonal sales figures for 1995 come as a bit of a disappointment to the Acorn board. The company has still sold some 70,000 machines as a good proportion of adopters from 1992/3 decide to upgrade, but there were some heady sales projections being bandied about in the autumn prior. Acorn's share price takes a hit, and a company-wide re-organisation is put in place. The primary consequence is the complete decoupling of chip designer ARM. What's left of Acorn is then organised into two distinct divisions: Workstations, which continues the hardware business, and Open Acorn, aiming to further develop and expand the reach of RISC OS. The latter hints at early talks of the "Network Computer" leading to rumours of an Acorn designed box with a custom RISC OS ROM, whilst the NewsPAD, leading a European initiative for a portable multi-media viewer, becomes something of a minor success.

Development of the successor to the Risc PC is begun, and there is an urgency about the project as the venerable slice-based desktop began life with a 33MHz bus and the latest StrongARM processors run at 233MHz, hampering its performance. Project Phoebe promises a revised internal architecture and more developed StrongARM processors, as well as utilising current PC standards. The four PCI slots will come in useful...

With the internal reorganisation and increased research and development, although revenue dips to £65m, profits are down to £1.2m, albeit with much ink spilled proclaiming it's all about investing in the future.

1997

There is an air of optimism abound in the world of RISC OS as the launch date for Phoebe is set as September, just in time for the European Computer Trade Show at Olympia. And there is even better news. After a chance encounter at the show (19), it is soon announced that 3dfx will support RISC OS and, indeed, by the Christmas of 1997, the first Voodoo graphics card arrives. In the short term, this places the Acorn range on a par (in capability if not quite in price) with regards gaming compared to the Windows PC, the consequence being that there is a minor surge in PC ports to the system.

|

| Ironically from the issue of Acorn User that said it was cancelled. |

It's not all good news though as the successor to the A7000 series (imaginatively called the A8000) are announced, again with two models, and it's almost instantly apparent that the base machine is being ignored. There isn't much of a requirement for a hobbled £500 general computer that really shouldn't be plugged into a TV, and the better spec pushes the price close to £900 that also includes a monitor. There is a general shedding of users as they jump to Windows and, later, the revitalised Mac, but enough remain on RISC OS to make Phoebe, at least, a relative sales success.

1998

Financial results for 1997 reveal some good and bad news. The A8000 is a flop, whereas Phoebe pushes past 50,000 units. Revenue is down to £51m although profits are a relatively healthier £4.1m, reflective of the high end desktop sale and a steady push of RISC OS into embedded markets. The last of the tail end early 90's adopters upgrades to the latest hardware and it's becoming clear that the heady days of six figure sales numbers per annum are long gone. To those in the know, there is a general feeling of managed decline creeping in, and before the end of the year, the A8000 is cut to a single spec only, just to retain a sub-£1,000 machine.

1999 to 2002

And managed decline it is, as although there are processor upgrades for Phoebe, there is no replacement desktop planned. The failure of the Network Computer initiative isn't a stunning blow to Acorn, and the decision is made to sell off the set-top box unit to Pace Plc, also giving them a licence for the OS. It becomes apparent that the future of the company is more assured via software rather than hardware as the company posts its first annual loss in nearly a decade in 2000. In early 2001, what's left of the hardware team is disbanded, and the user base declines further into enthusiast niche territory. New machines do arrive from small scale manufacturers who can cater for sales in the hundreds, and it's only as the third year of the new millennium arrives that the last of the large games publishers abandons the platform, leaving the leisure market to solo and indie teams.

As for the OS, in early 2002, the decision is made to open source RISC OS. There isn't the revenue to support even the cut down Acorn that remains, and it at least assures the future of the operating system as there is renewed interest in a free, low footprint OS.

(wibbly wobbly screen effect)

Plausible scenario or complete bull hooks? It was reported at the time of Acorn's sudden hardware volte face in 1998 that the core business had essentially lost money since 1993, so any success with the A3010 would have had an impact. I don't believe it would have been enough to see off the competition coming from PC or Apple (post 1998), but it might have changed the circumstances of the company's withdrawal from desktop hardware. It would also have affected moves like the co-founding of Xemplar and the cosying up to Oracle. Maybe...

When it comes to counterfactuals, your original decision point, the locus of change from actual history to the alternate version, has to be believable. So it is that I have chosen Christmas 1992 as that point. Without the success of 92's festive season, Commodore would have collapsed even sooner, and given that almost every computer manufacturer has suffered from quality control issues and shipping delays then, well, why not? The company was fleet of foot when it came to financial efforts, sometimes desperately so, but it's not too implausible that they might have struggled to pay for components and set up a manufacturing contract in mid-92. It truly was a make or break event. The success of the A1200 briefly rejuvenated the Amiga range and bolstered the coffers of the financially mis-managed company, giving it breathing room to continue the CD32's development and sustain the Amiga brand. And yet it mattered not a jot past 1993.

According to David Pleasance (20), the decision to launch the CD32 in that year was made purely for revenue reasons and it hampered sales of the A1200. The issue here that even with the CD32, Commodore was failing, the console merely extending its death scene. That and without the 1993 release, there might not have been a Commodore left in April 1994 to launch anything. Nor would the CD32 have been the silver bullet even if it had made it to the US. The 1994 console market was rammed with new hardware: the 3DO and Jaguar were already out, Sega's Saturn and Sony's PlayStation were incoming, and I can't help but think that the CD32 would have looked extremely tired in comparison by the end of that year.

With regards to the era after the collapse of Commodore, I'd like to think the UK management buyout could have worked, albeit for a limited period. The CD32 would have needed a replacement within a year or two, and the A1200 wasn't exactly cutting edge in 1992. It most definitely wasn't when Amiga Technologies were trying to flog them. Would the new UK/Germany-centric company have had the resources for the full-scale development of both a new console and an affordable home computer? It's not beyond the bounds of reason, and maybe David Pleasance will tell us in his latest book, but having experienced the "joys" of the Kickstarter journey for From Vultures to Vampires" (the tale of the publication of those three volumes is almost as convoluted as the story they tell!), I will not be finding out that way, at least not yet. And if you have seen the updates on Kickstarter, you'll know about the one dated 6th September, he's already running behind and "we might be late reaching the printing stage." Cynical me now awaits the announcement that due to the staggering amount of material, a second volume priced at £35 plus postage will be coming...

For Acorn, it's 1990's behaviour smacked of that must abused term (guilty, your honour) "managed decline", which is why it comes into use as the decade closes in the counterfactual. The ubiquity of x86 hardware and Microsoft's business practices meant that the DOS/Windows compatible was the general computing platform of the decade. Add in SVGA, soundcards, CD-ROMs etc, although you'd spend more money, you also gained greater capability. Even Acorn noticed this with the introduction of the A7000 range - these were priced similarly to low and mid-range PC's, following the pattern that the entry price point for a home computer had moved from a few hundred to nearly a grand, and you had to include a monitor as resolutions had advanced way beyond what your standard TV could handle. You could spend less, but that could often be false economy. The RISC OS high end was catered for by the Risc PC which for a short period could go toe to toe with the PC. However, the rapid development in the PC world meant that window of opportunity was exceedingly small. It would also have taken a degree of prescience few people have for their management team to make the "right" decisions every time.

As the decade closed, only Apple remained as an alternative to the Windows PC, rejuvenated as it was by the iMac (as well as a change of leadership. $150m from Microsoft and the timely sale of some ARM shares), demonstrating what a combination of in-house design and careful tech choices could achieve (excluding that pucking mouse - not a typo!). Acorn had proven in could do the same (my affection for the Risc PC design is well known, at least by regular readers), but Acorn was too small, and even the once hugely successful Apple flirted outrageously with financial destruction as the decade progressed.

Anyway, none of this really matters now except as the occasional day dream and pondering. I have more important things to do like maybe fire up my RISCOSbits PiRO Noir or Pinebook Pro and enjoy the best of what RISC OS still has to offer. Might I humbly suggest that you give the OS a try too...

1) ST Format Issue 35 - June 1992

2) www.dfarq.homeip.net/commodore-financial-history-1978-1994/

3) Acorn User Issue 119 - June 1992

4) Acorn User Issue 150 - Christmas 1994

5) Commodore: The Final Years

6) Amiga Format Issue 38 - September 1992

7) ST Format Issue 46 - May 1993 - in this counterfactual, Atari pretty much continue as they did.

8) ST Format Issue 40 - November 1992

9) CU Amiga Issue 32 - October 1992

10) Computer and Video Games Issue 132 - November 1992

12) Amiga Format Issue 53 - December 1993

13) ST Format Issue 46 - May 1993

14) ST Format Issue 50 - September 1993

15) ST Format Issue 52 - November 1993

16) ST Format Issue 58 - May 1994

17) Amiga Addict Issue 24

18) This would be similar to the Stork design from 1996 but two years earlier.

19) Interview with Andrew Rawnsley of R-Comp Interactive 04/02/2023

20) Amiga Addict Issue 24

Saturday, 16 November 2024

Magazines of Yesteryear - ST Format Issue 46 - May 1993

Oh, ST Format, what were you thinking? The proclamations, the hyperbole, the... desperation? Six years before the Matrix and someone had definitely taken the blue pill...

It is indisputable that when the Atari ST arrived in 1985, it shook up the home computing market. However, by the time of this 1993 issue of Future Publishing's ST Format, things were not so rosy. A lack of focus, bad business decisions, and a complete disregard to actually developing the platform during the intervening period (something rivals Commodore were similarly guilty of until what turned out be a last desperate attempt with their 1992 refresh) had hammered ST users and it was pretty clear that the platform's days were numbered.

Unless you believe the cover. And, gentle reader, you really shouldn't.

Straight in with the news and the announcement of a £90 price cut to the STFM! Ok, not exactly a price cut per se given that the machine had been out of production for over a year, but a re-introduction of the base 512Kb STFM that originally launched in 1986 at a highly attractive price of £159. Sure, but even a reader back then should have questioned a) what the market was for the thing and b) just exactly how much was Atari going to make as a profit off such a low figure. The claim of 150,000 sales in 1993 sealed the deal. Whatever they were drinking at Atari HQ, it had a hefty percentage on the label. "Well placed" sources also stated that the 520 STE would drop to £199 and the 1040 STE to £249. There is a feature about the STFM later on which we'll get to, but for now... I'm pretty sure the Bearded One would have been weeping on his bike.... And as for the cover shout, no, there were not 150,000 new users, there was no additional stock on sale yet and... You get my point.

In other news, peripheral and software provider Gasteiner were being threatened by Sega over the use of the name Mega Drive, with the former giving their ST hard drives that moniker, and the latter, well, you can guess.

There's also a brief report on the 7th International Computer Show, the most interesting (meaning laughable) tidbit being the 286 PC emulator board for the Falcon. Yeah, it was planned to be cheap (£200), but a 286 in 1993? In the PC world by this time, the 386 was making way to it's more advanced successor, and of the big name manufacturers in the UK market, only Amstrad, IBM and Olivetti still had some bargain basement 286's for sale.

A brief round up of the latest software available for the Falcon proved that some people were trying with the 32-bit wonder machine even if Atari really weren't, before we get to the first of the features: using your ST for productivity purposes. Word processing, programming, desktop publishing, and music are just some of the uses still valid for your 16-bitter, and the following round up of external floppy disk drives would have been handy for both serious and leisure users, given that multi-disk games were very much a fact of life now. Only one drive was high density capable, but it cost nearly twice as much as the double density competition and was only suitable for Mega STE and TT owners.

We detour through some gaming guides and a platformer round up before reaching the STFM future feature. It's all spun very positively for the audience, maybe to cheer them up as they see their favourite computer fall behind. There's a funny little graph focussing on Gallup reported software sales, with the ST coming out on top with 5.7% of total software sales in 1992. The other formats featured include Amstrad's then out of production CPC on 3.9%, Atari's own Lynx at 0.7%, Sega's Gamegear (which had only been out since April 1991) at 4.4%, the NES at 4.6% and the SNES at 3.7%. Considering the latter arrived in the UK in April '92, I'm not sure the graph passes even the most cursory of examinations, and what about the other 77%?

A second graph showing ST sales over the years is another "awww, bless" moment, and, you know what, good on ST Format for trying. I mean, this initiative would go nowhere, and the ST would effectively be abandoned before the year was out, but you've got to admire the optimism. It's not all one sided happy clapping, and the comments from devs and retailers are extremely telling, with one HMV sales rep saying that in some stores, Mac software was outselling ST offerings. Ouch!

Still, there would be a follow up piece in the next issue, but that does not concern us today. Instead, to the games!

Civilization racks up a deserved 92%, whereas AV8B Harrier Assault falters with 62%. The Greatest, a compilation featuring Jimmy White's Whirlwind Snooker, Lure of the Temptress and Shuttle (talk about varied), scores 91% despite the latter title really not matching the quality of the other two. Six other games are also rated, with No Second Prize reaching the heights of 87%, and Wild Streets plumbing the depths with 38%. Nine reviews in total. Meanwhile, in the corresponding Amiga Format, there were 9 full-price reviews (including Lemmings 2, Walker, B-17 Flying Fortress and Chuck Rock 2), 9 budget offerings and two compilations. Intriguingly, the Amiga version of The Greatest swaps Shuttle for Dune, and I think Amiga owners scored there.

Back to the ST, and there's serious software too. Desktop Publishing stalwart Calamus has a new version, Calamus S, achieving a 91% score, 3D Construction Kit 2 almost matches it at 90%, and Convector Professional 1.00J slightly disappoints with 75% but gains kudos for the Airplane gag in the review title.

Canon leads the way with hardware, its BJ-200 bubblejet printer rating an excellent 92% (albeit for £468.83!), whereas Spectravideo's Freewheel steering wheel only manages a steady 76%. A duo of screens finish off the hardware, both with scores in the 70's. Silica Systems were flogging a Viewtek 12" greyscale option for £69, and comes across as a great medium resolution mono option. Gasteiner, however, want £149 for their 14" VGA mono offering, which the mag thinks is a tad over-priced for a high res option, but nonetheless not too shabby.

Several pages of Public Domain software follow up, as do tutorials for Crack Art (an art package which desperately requires rebranding), and assembly programming. The usual letters page provides company to a readers art gallery section, before we hit the final page and obligatory humorous End Zone.

And now, a break for commercials:

The First Computer Centre has pride of place as soon as you open the mag and they'd see you right for your ST hardware needs. A barebones Falcon would set you back just under £600, but a useable spec would bump that to nearly a grand! Not to labour the point, but in the DOS world, that dosh would get you a well-specc'd 386 and another £50 to £100 would guarantee a 486/25 with the same amount of RAM but double the hard drive space.

If funds were more limited, the existing STE range would be yours for £229, although bumping the RAM to at least 1 meg was advisable. The 1040 Family Pack looked a bit better for those wanting to do more than just play games.

Other formats were available too, starting with the Amiga, and the fact that the A500 Plus was still being advertised (as well as being £50 cheaper than the "better" A600), shows that the big C really fucked up the low-end switch. There isn't an HD-free A1200 though (maybe trying to shift the remaining 68000-based stock or get Falcons out of the door?), but you could ask about Archimedes pricing, which at this point would have meant the A3010 or maybe the A4000... And let's not forget about consoles - that Mega Drive plus Sonic or Olympic Gold for £125. Bargain for the time, and a sign that no matter how cheap the ST could do, if it was just games that kids were interested in, consoles were the better option for most.

There's a wide array of printers too, from the evergreen Star LC20 to more heavy duty laser options, and at those prices, you really needed a genuine use case to buy one. Finally, for those of a professional bent (or just wanting something better than a TV), the selection of monitors reveals the period defining Philips CM8833 in its Mk2 guise, as well as a couple of high-res mono monitors.

Special Reserve have a couple of pages dedicated to their ST wares, and there's many a worthy title on offer. Quite a few under a tenner too, and that Lynx 2 appealed to me back then, even though I never had the cash to spare at the time. What is interesting is that they don't have any actual Atari computers to sell. Some accessories, disks and the like, but no ST hardware. Hmmm...

Ladbroke Computing were, however, another hardware dealer and they could set you up with a 520 STE for £219. Ok, so a few quid cheaper than The First Computer Centre, but you have to wonder what exactly were the profit margins when a punter walked away with a box, but there again...

The newsworthy Gasteiner were cheaper still, with the base STE at just £209, and that 4/65 spec Falcon for £899! You'd still need a monitor on top of that to get the best out of the Falcon, and that would have taken the overall package well into 486 territory.

Rubysoft have a dual-format software listing advert, with ST and Amiga versions listed where appropriate. This was not necessarily a good thing as it highlights exactly which games you couldn't buy on your favourite home computer. There again, you'd already have some idea of that by this point just by rocking up to your local games store... when such things existed.

Eagle Software are another games retailer, although this time with a focus on ST-only releases. As you can see (possibly with the aid of a magnifying glass), the ST library was large and varied, so even new buyers in 1993 would have had a good array to choose from. Not many new games, granted, but a hefty back catalogue.

Naturally, it wouldn't be a 1990's magazine without a Silica ad, and here they show off the main sellers Atari were offering. Not the cheapest by any means (see above), at least the adverts were packed with information which would help those all important buying deliberations.

So there we have ST Format. Still kicking with 108 pages in total, and an ABC of 62,210 (July to December 1992). That ABC was down from a high of 70,258 in early 1991, dipping to 65,202 in the second half of that year, rising slightly to 69,059 in early 1992. However, this particular issue would be in the 52,810 bracket, and as the ST's fortunes declined, so did this magazine's readership. Nothing new there, and although the final ABC figures were for the second half of 1995 stated a circulation of 14,379 readers, the mag itself last until its September 1996 issue, by which point it had outlived the ST, the Jaguar and Atari themselves. No shame there, and a good run for the Future-published periodical.

Where to next, I wonder...

Saturday, 9 November 2024

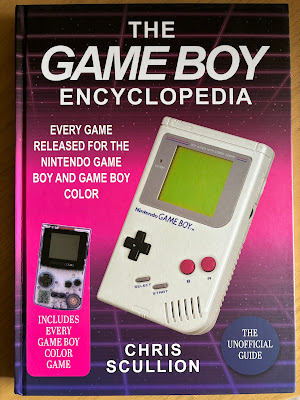

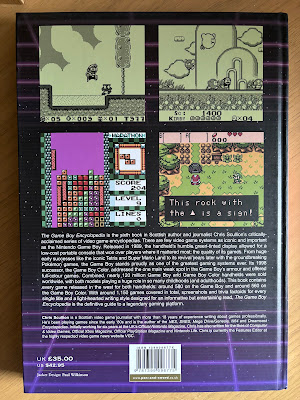

The Game Boy Encyclopedia by Chris Scullion - Book Review

Sunday, 27 October 2024

The Mysteries of Monkey Island by Nicolas Deneschau - Book Review

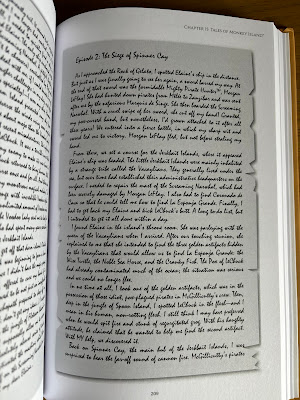

Ah, the Point and Click Adventure. A genre I've loved ever since the days of my Amiga 500, a genre I still love to this day (my 12th P&C adventure review for Fusion is in issue 61 and there's a couple more on the way for them too, demonstrating how vibrant the form is to this day, especially amongst Indie developers), and one where my first steps were taken on Melee Island. This is where Nicolas Deneschau's 300-plus page opus from Third Editions comes in.

If you've ever wanted to know the history of the seminal series in one place, then this is the book for you. You'll first notice the high quality of the book itself - a hefty tome with a clean presentation and well spaced text. There are few illustrations, but those that are included are top notch and fit the subject perfectly, and a foreword is provided by Larry Ahern, co-director of Curse of Monkey Island.

The layout of the tale is pretty straightforward, gently easing the reader in with a potted history of Lucasfilm Games, the move to point and click adventures, and the creation of the SCUMM engine. From there, each title is detailed in chronological order, with cursive text boxouts offering Guybrush's diary of what occurred in each release.

From the beginning, there is very much a personal angle from the author, and as a long time M.I. player, that approach resonated highly with me. This isn't just a history of the games themselves, but also of the state of gaming at the time, how people played games back then (disk swapping, urghhh), and how the market changed as the series evolved.

Much research has been carried out and there are numerous footnotes pointing you to original sources. The author also uses footnotes to relate personal experiences and commentary. Many of these are funny, if not down right hilarious and adds greatly to the overall personality permeating the writing.

There is plenty to learn here, especially about the movie adaptation that was once mooted, and of course the story doesn't end with the third game, Curse of Monkey Island. No, from there we move on to the Telltale Games entries and beyond, finishing with the most recent of the series, Return to Monkey Island. All the while, the narrative is interwoven with quotes and amusing bon mots, and it's almost a shame when you reach the last of the main chapters, as you realise that you've more than enjoyed the company of Nicholas. That also draws attention to the quality of the translation: it is superb!

Four appendices finish proceedings off: the first details the insult fighting replies from the first game, the second offers potted biographies of key individuals, the third lists the classic adventure games from LucasArts, and the fourth contains the lyrics to "Plank of Love".

This was the first book from Third Editions that I'd heard of, courtesy of a tweet from Konstantinos Dimopoulos of Virtual Cities fame. Having checked out the other titles from the publisher list at the back of this volume, and having enjoyed this one so much, is it any surprise that I ordered another book from them, this one heading for Uncharted territory...

You can pick up a copy of this and other Third Edition books from Amazon. Bear in mind that as a UK customer, there is a bit of a wait between ordering and delivery but such is the way of things, and it would be a shame for anyone to miss out on such a well written, heartening narrative of one of the best games series ever created. You can also follow the author on X - @Nicozilla_FR.

A review of this recent arrival will also be coming soon (well, as soon as I've read it...).

Saturday, 5 October 2024

Magazines of Yesteryear - The Mac - Volume 5 Number 1 - January 1997

Mac Kit to Die For??? Maybe, but given this issue of The Mac hit the streets in early December 1996, maybe it should have read "Mac Kit Apple is dying from!" You'll understand why once we get to the ads...

The news pages lead with the triumphant announcement that Apple had returned to the black in its final quarter of the 1996 financial year. The piece states a $25m profit against expectations, which when you consider the Q2 loss of $700m, combined with a Q3 loss of $34m, any positive number was a good thing. CEO Gil Amelio had previously boasted that Apple would by out of the red by Q2 '97, so they were early achieving that. However, revenues were collapsing and the 1996 as a whole would see losses totalling $816m. That, gentle reader, was just a taster. It's no great spoiler that Apple's '97 expectations were hammered with a loss of over $1bn, before a turnaround in '98 with a $309m profit. Fear not, fans of fruit based computing, they made a profit of $96.995bn in 2023. As Mr Watson warbled, "It's been a long road..."

Also in the news was Apple's desire to double growth (uh-oh...), as well as ongoing confusion of Apple's OS issues. Apple had also cut 65% of its authorised reseller network which shocked no one as there were plans for Apple to open its own retail stores. That didn't pan out (you can guess why), with the first Apple Store only opening in the US in 2001. The UK got its first Apple Store in 2004.

Internet Explorer 3.0 (those were really not the days, my friends, I'm glad they did end), was now available to Mac users, as was the link kit to connect Palm Pilots to Macs. Having written about Palm PDA's both here and in Pixel Addict, all I can reiterate is that they were brilliant devices for their time. Meanwhile, Iomega were planning a new compact storage format that could fit a 20Mb on a 5cm by 5cm cartridge. Heady tech for the time (seriously), this product was crying out for a cross-marketing campaign about N*Sync-ing your data via your N*Hand cart. My talents are wasted, honestly...

Reviews next and first up we have FreeHand 7, rated "the best drawing tool available", which probably validated its price tags of £450 and £646.25, depending on which add-on it was bundled with.

Apple's latest Power Mac, the 4400 comes under the spotlight and come just over the grand mark (£1,056 inclusive of VAT, £899 ex). A score of 4/5 is pretty good, and for the time that was a reasonable ask. As technology advanced to new generations of processors, the asking price of a decent machine rose. By late 1996, the idea of a general home computer for less than £500 was having a rest as the rise of advanced new processors (Pentium, PowerPC and StrongARM) meant that new desktops had settled around the £1,000 mark, albeit temporarily as the latter half of the decade saw prices (in the Windows world at least) tumble - all helped by the tussle between AMD and Intel.

More Apple kits gets the once over with what appear to be advanced looks at the MessagePad 2000 and the eMate 300. Let's get this clear: by this point, the Newton had matured into a reasonably capable platform if you wanted to have computing on the go without the bulk of a laptop. Sure, smartphone users today will fall about laughing at the size of the revised PDA but for the time, this was serious kit. The StrongARM SA-110 was a powerful leg up for processing power, and the software offering was in a much better place compared to the original Newton. That being said, with an expected price of around £750, it was still a ton (or several) of money for something that merely acted as an extension of the desktop/laptop experience.

Not so the eMate 300, and I have to admit that this piece of portable tech was something I really wanted to get my hands on back in the day. Effectively placing a Newton into a laptop style case, the idea was sound, even if the size of it was off-putting for school use. Compare the eMate to the Alphasmart range of devices. The latter were smaller, lighter, lasted longer and were more suited to being mishandled by children. They were also cheaper, an important consideration when it comes to bulk buying. Still, the eMate was a sexy bit of kit and its failure was not down to the concept. The execution was ok, but Apple, being Apple, decided it was for education only and missed an opportunity to widen the user base. But hey, this was mid-90's Apple, it was a shit show anyway...

Games reviews kick off with Actua Soccer for footie fans, and Marathon Infinity from Bungie. Considered flawed and the weakest of the Marathon trilogy, Bungie would move on to other things, including an eventually un-released real time strategy title codenamed Monkey Nuts, eventually morphing into the original Xbox launch title (and all-round classic, Halo: Combat Evolved).

There's also a review of Avara, an online multiplayer shooter that, whilst looking basic, appears to have neatly given gamers a taste of fighting the world. Well, as long as you had at least a 28.8kps modem. 14.4kps was a tad slow, and even the higher speed option could struggle with lots of players! Early days, people, early days.

Zork Nemesis would keep adventure fans happy, and MechWarrior 2 proves that ports from DOS can work on the Mac, and be the better for it.

An end of year issue is never the same without the Reader's Awards section and it's no surprise that Apple win the Mac Manufacturer of the Year award. Ok, that sounded sassy, but the clones were beginning to make themselves known on the market and, as noted above, would not help keep Apple afloat. Demon Internet (remember them? Ah, the good old days) won Internet Service Provider of the Year, Netscape Navigator best Internet Software, and the Iomega Zip for Best Storage Device.

There is a "How to buy a Mac" guide that is a time capsule of how things used to be when buying a computer, though the near-traditional advice of "use a credit card if you can" still rings true to this day.

A round up of 17-inch monitors is guaranteed to take your breath away, and not only for the prices (the Applevision 1710 at £830 inc VAT was cheap for a Trinitron tube, but expensive in this round up), but also for their weight. The 1710 came in at 49lbs (22.2Kg) for a tube that could give you 1280x1024 at 75Hz. Good spec and picture quality, but this was not something you moved around much. The 1710 takes away the Not So Cheapo Editor's Award, whilst the £527 CTX 1765D snags the El Cheapo prize.

A proper "how quaint" moment now with coverage of the DVD (Digital Versatile Disc) format. Very early days here for the wonder disc format but it would prove successful. I can still remember popping into Dixons in Kingston Upon Thames in 1997 and seeing a player for sale with five movies (the only five at the time, I think), with naff all change from a grand. As an impoverished student (who'd blown a fair chunk of his student loan on an N64 and Turok!), all I could do was gaze in wonder.

The how to guides section gives us advice on Self Assessment completion for your tax concerns (yay?), and how to sort your travel plans on The Net. Such a charming term, The Net, redolent of dial up modems and eye-shrivelling website design. There's even a box out on finding your search engine first: Alta Vista was apparently the fastest, but Yahoo and Lycos were easier to use. Compare and contrast to the absolute shit show that is Google these days... Yeah, if there was ever yet another example of how the drive for greater revenues fucked things up, Google search is up there with the most egregious.

e.Zone takes a look at the online goings on, the highlight being an interview with William Gibson. There's chat around his then-new book, Idoru, and his love on the Mac, although he believes his next Mac would be a clone. It might have been, but the next one after that would have been a Cupertino original.

A guide on how to succeed at Warcraft II is followed by some Q&A pages, before the buyers guide takes up pretty much the rest of the remaining pages. As is decreed in the ancient by-laws of computing magazines, the final page is a humorous look at the year just gone, and rather funny it is too.

(Deep breath)

So..... Apple wasn't in great shape as the count down clock to Millenium Armageddon hit 36 months, and if you want a reason why, I give you this page from Apple dealer, Gordon Harwood:

Can you see what I mean? Which model? Which spec?

Let's say you have £1,500 to spend on a Mac, and yes, I know, that was a lot of money in 1996/7, but the nature of computing had pushed prices up between 1994 and 1997 as new processor tech and add-ons like CD-ROM drives, graphics cards and modems arrived. Every format saw spec/cost inflation in the middle of the decade, and £1,000 seemed to become the de facto entry point. For this example, you have £1,500 which, as a consumer, meant £1,275 before VAT.

Now let's check out what GH could offer. That Performa 5320 with a 15" built-in monitor looks decent, although the printer bundle would take you just over your budget. But wait! The Performa 6320 doesn't include a monitor as standard, but the bundle with a 15' doofer (minus the multimedia TV shenanigans) was yours for £1,280 and you got a keyboard with it. More RAM too, but no modem, but you still had cash to spare. Why the emphasis on the keyboard inclusion? Look closely, and you'll see that the very cheapest of each of the Performa ranges (5320 excluded) do not include a tactile terror. Nor a monitor, come to think of it, so yeah, the initial price looks cheap for a Mac, but to actually buy a usable desktop? That 6320, starting at just £799 ex VAT. Nope. That'd be £1,089 ex for something you could use out of the box, and to be honest, you'd spend the extra forty odd quid on the 15" option.

You could argue that Apple were merely catering for all possible users, so upgrading peeps might already have a monitor and keyboard. You could also say that they were nickel and diming the customer in order for their good to appear cheaper. A mix of both maybe? Not that it matters now, but it does hark back slightly to PC box builders in the first half of that decade advertising machines without an OS. It knocked anywhere between £50 and £100 off the headline price and was only noted in the "optional extras" section. An operating system... optional...? That practice soon ended. However, if they could make "A.I." optional in modern OS's, that would be just great, thanks. Unless they can make it genuinely useful and not just some data slurping funny picture generating boondoggle. Alas, I fear not.

A Powerbook was just within reach - ok, maybe a couple of quid over, but a Power Mac was also just about do-able if you took the very base option, as you didn't get a keyboard or a mouse. Going back a couple of paragraphs: really, who the actual fuck ships a grand and half computer without a f-ing keyboard?

Anyway, on to Computer Warehouse and the really damning evidence of why Apple was two steps away from Destination F*cked. The first two pages concentrate on the top of the range clones from Power Computing. These were often as not as expensive as the equivalent Apple product, but they were also often faster and offered greater expansion opportunities. Not see the threat yet?

How about mid-range, and the Power Center 132MHz 604, 16MB RAM, 1GB hard drive and 4x CD drive. No monitor or keyboard, but yours for £1,499 ex. A couple of pages on, Dabs Direct had Apple's equivalent, the Power Mac 7600/132 (1.2GB drive and 8x CD) for £1,649 ex. That £150 could go a long way, even with the slightly lower storage and slower CD drive. And yes, it gets worse.

Switching to Dabs Direct, the full Mac range from Apple is here, as are the clones from Umax. If money was really tight, then Umax could do you proud with it's range, starting at £799 ex. You could argue semantics about value and mandatory add-ons, but the point here is that Apple, whose bread and butter was computing at the time, was in direct competition with box builders who could sell roughly the same kit but cheaper.

There was another fly in the ointment: confusion. Check out MacLine. On the page to your left, a goodly selection of Mac models, bundles and offers - but only a selection. On the right, the Umax offering. ALL OF THEM. Two ranges, three models a piece, offering six separate price points, each easily discernible from the others. Now look back at what Apple were trying to hoof out of the door. It's a mess. You had ads featuring the Performa 5200 5260, 5300, 5320, 5400, 6320, 6400, and as for the Power Macs, there were the 4400, 7200, 7600, 8200, 8500, and 9500 models. Never mind the different configs per model, the number of models was mind-boggling.

Just to hammer the point home, even the buyer's guide notes how great the value is with the clones. In the sub-£2,000 bracket, clones outnumber Apple machines by 9 to 5, it's evens in the £2-3k range, and Apple are dwarfed by 10 to 2 in the £3k plus spectrum. In each area, Apple was having to fight to retain any semblance of value for money, especially against Umax, and that's not what the clones were meant to do.

It wasn't all hardware though, with MacGold Direct sorting you out for software, including a rather impressive range of games and entertainment titles.

And that's it for The Mac in 1996. Bit of a weird one, and not just because of the fashion on show (or the full page ad for Maxim magazine...), given that on the surface it looked like things were getting better for Mac users, but in actual fact, the platform was close to dying simply because the host organism was unable to do the one job it really had to do. It would take a year or two and a lot of red ink, but Apple would turn things around, surprisingly so. But that never happened for the format I'll cover in the next MOYY.

|

| The more tame section of mid-90's fashion. |